Baseball Bunka

I return from Osaka after a nice long weekend of sightseeing, sampling of local cuisine, and contemplating the role of baseball as a part of Japanese society. My short stay in Japan's most free and individualistic city turned up more than a few glimpses of the intersection between baseball and traditional culture. I'll present a snapshot of my trip, with a special emphasis on the baseball moments that I enjoyed.

Osaka is Japan's 3rd largest city, with a population of just under 3 million people. It is a metropolis by any definition of the word, and the people enjoy the benefits of big city life. They also suffer from some of the typical pitfalls of urban excess. My impression of this vibrant community is similar to my affection for my native New York. It's a place where good food, good drink, and colorful characters are found at every turn. The local sports culture is rabid, and the fans take their Hanshin Tigers very seriously. The cheering section of that club is as loud and boisterous as any found anywhere in the world. The Spring Sumo Tournament is held in Osaka during March and draws a very supportive and passionate audience as well.

Sampling the famous local cuisine was, of course, a highlight of the trip. I ate

"okonomiyaki" which is like a pancake made in front of you on a teppanyaki grill. It's filled with various things depending on your preference, and the name actually means "whatever you like, cooked-up". I shared a seafood pancake and a cheese pancake with my wife on my first night in town. Good stuff with a frosty mug of beer.

I also made my way to the highly entertaining section of the city called

"Dotonbori" where neon is used like it's going out of style, and the wackiest elements of Osaka culture are out in force. It's a place famous for crab, ramen, and takoyaki.

Takoyaki are basically balls of batter and octopus fried into a kind of dumpling. If you've ever had a New England crabcake, replace the crab with octopus, and voila...takoyaki.

There's a lot going on in Dotonbori. Icons of Japanese popular culture are both created and celebrated in the flashy environs of the street malls. It was here that I photographed the most gigantic version of the NTT (Nippon Telephone and Telegraph) ad campaign, spanning the entire height of a building. The recent campaign touts the high speed broadband that NTT uses to provide reliable and clear service to anywhere. Ichiro Suzuki is the poster boy, in full Mariners regalia, and has his ultra-cool poster boy face in effect. My wife noted as we stared at the giant hommage to Ichiro that he's always concerned with appearances, including his endorsements, while Hideki Matsui is always playful and at ease in pajamas, traditional summer robes, or serious in his Yankee uniform.

That was hardly my only brush with baseball during the weekend. I have to backtrack to when the whole trip began to tell the story.....

From the plane I looked down on a glimmering night scene, with both neon splendor and the gentle glow of homes and apartments in the middle of the city. My eyes immediately were drawn to Osaka-jo (pictured above), or Osaka Castle as it's called in English. The castle is one of the centerpieces of the city and a national cultural treasure that is often used in tourism promotions and the like. It has an important role in the unification of feudal Japan, and the Osakans revere the traditional grounds with great respect. The interesting point to this story, is that the illuminated castle was flanked on 3 sides by illuminated baseball fields. It was at that moment that I knew my 1st day's itinerary.

Touring the castle and its grounds was fascinating. I'm a history buff, and I felt connected to the events of history that took place on the very ground I was standing. As I learned more, I realized that some of the most important battles in the unification of Japan were fought on the soil upon which I tread, and the blood that was shed, in some way, was responsible for the current order of things. The castle itself is beautiful and one is treated to a display of artwork, architecture, and history on each of the 8 stories of the stronghold. From the 8th story observation deck I circled around to the West to find the baseball field that I had seen from the sky the night before. It was quite large for a public park, and I could clearly make out that it was something of a huge sandlot. The juxtaposition of the ancient castle ornaments and the baseball grounds in the distance made a nice photo.

From the castle I bolted for the field. I wanted to see what was going on there, and what kind of facility the city of Osaka had provided for its citizens to enjoy the great game of baseball. To my surprise it was quite spartan and bombed with graffiti. There was the requisite X-rated graffiti featuring male genitals, and there was also a poor rendition of Mickey Mouse on another concrete wall. Go figure. I wasn't sure what to make of the riff-raff that was hanging around outside the grounds. There was a mix of moms with their little children, chain-smoking salarymen with big dark circles under their eyes, and even more suspicious looking characters in yellowing golf shirts kind of moping about. I stopped to take in the practice that was going on just inside the walls. There were kind of portholes cut out of the concrete backstop, and it was apparent that they were the best views in the house for the loitering fans. The guys taking batting practice against live pitching seemed to be part of a local amateur team just out for a little sunshine and some exercise.

I made my way around to the far side of the stadium to get a clearer look at the practice from the opening in the left field fence. It was there that I got my best view of Osaka Castle in the background, looming as the players took their reps. A handful of junior high school players, in their uniforms, were waiting around on their bicycles for their coach to arrive and start their afternoon practice. I approached them and asked if they practiced here everyday. They replied that their practices always took place on the grounds, and that they in fact played everyday in the shadow of the castle. I thought it was a powerful metaphor for the game that unified Japan on the grounds of the bloody war that defined the course of that same nation. Could any of those warlords, or any of their soldiers, have imagined that the battlefield where they lost their lives and struggled for ultimate control of the riches of Japan would one day be a symbol of populist life, and an arena dedicated to a game brought to Japan by missionaries centuries later.

In the end, my short stay in Osaka did not include a professional baseball game, as the home team was out of town. It was more a complete cultural experience with a lot of exploring on the menu. Baseball was hardly the main attraction of the time in the vibrant city, but it was also something impossible to escape. If the people of Osaka, and other cities all over Japan, nestle their sandlots and stadiums in the heart of their most important cultural zones, it's not difficult to imagine how much the game means to the identity of the Japanese. It's also one of the reasons I feel so at home here despite the octopus cakes and typhoons. Long live baseball!!

Risk Factor

With the notion that Daisuke Matsuzaka may be posted and join a Major League ballclub in 2007, there has been an increasing buzz around the internet and in the major media outlets about the risks involved in paying big money to a Japanese ballplayer. I'd like to examine those risks here to put them in perspective, and offer some thoughts on where they may come from.

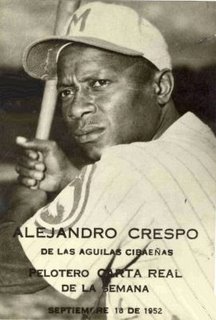

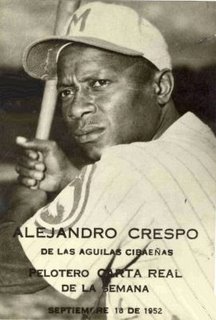

Some years ago, Latin ballplayers were looked down upon and many Major League teams refused to sign or play them. It was a lot of bigotry and a healthy dose of ignorance to the level of their play as well. Please, look at this snippet from the website

Latino Baseball Players:

"Players of Latin American heritage have a deep ardor for the game of baseball, and have made immense contributions to the national pastime. So many great players have come out of Latin America and seeing them playing shows how integrated the sport of baseball has become. Three to four decades back baseball didn’t approve the Latino players. As a matter of fact the Latino baseball players were the victim of similar negative perceptions and discrimination that many of the early black players had to undergo and triumph over. For instance, the Yankees gave up their superstar Vic Power, a Puerto Rican due to his dark complexion and due to his courtship with White women. In 1954, the Yankees traded him to the Philadelphia Athletics. With his new club, he became a constant All-Star. Following the decade of 50s the budding of Latino baseball players increased significantly. Currently, 30% of Latino players form the dominant force in the Major Leagues. Stellar performances by Latino players in the major leagues have dismissed the myth of the inferior talent of athletes from Latin America. For all the baseball-loving Latinos who are proud of their roots and culture it is a great satisfaction that the dignity of their culture has always been maintained by Latino big-leaguers and the stars of the present. Today, Latinos make up a significant portion of both the Major League Baseball player and fan bases. As of Opening Day 2005, 204 players born in Latin American countries were on Major League Baseball Club rosters accounting for nearly 25 percent of the overall MLB player base. The Dominican Republic led all countries with 91 players, followed by Venezuela with 46 and Puerto Rico with 34. The contemporary Latino megastars like Juan Gonzalez, Sammy Sosa, Bernie Williams, Vinny Castillo, Ivan Rodriguez, Pedro Martinez, Orlando "El Duque" Hernandez and many others with their will and determination have proved that they are no more less than any other white American player. This brilliant constellation of stars, in their full swing has become the most wanted of their respective teams and admirers. Sammy Sosa has become the preeminent player of the Chicago Cubs and Alex Rodriguez in the uniform of Texas Rangers has encouraged every slugger. These two Dominicans have proved that they lead the pack of Latino players followed by the Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Venezuelans, Mexicans and Colombians."The players mentioned in the article are a bit out of date, but you could easily replace them with David Ortiz, Vladimir Guerrero, Johan Santana, and others and all of the above would hold true. We have witnessed a boom of Latin influence in baseball over the last few decades that has reinvigorated the sport and increased the talent pool significantly. It would be beyond insane for anyone to question the level of talent that Latin players possess as a group. Why is it then, that a Japanese player's name is mentioned and people immediately conjure up Kazuo Matsui and Hideki Irabu and their chief examples? Why is it that people aren't more excited for their teams to bring over the next Ichiro or the next Hideki Matsui? In fact, why do fans ignore the possibility that they may be treated to the next Pedro Martinez or Johan Santana when their team pursues a talented young player from the East?

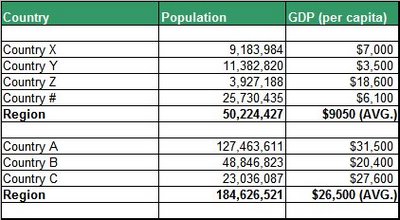

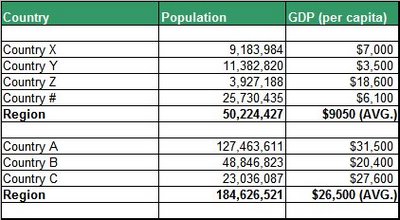

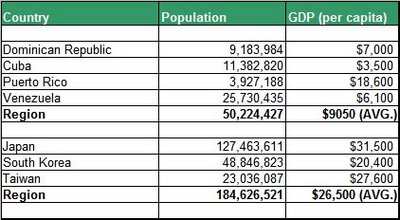

I'd like to present the following chart to preface my next point. Please click the chart to enlarge:

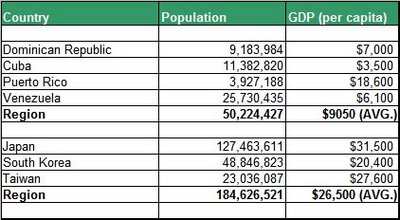

You see four countries in the first group. They have a collective population of 50 million+ people and an average per capita Gross Domestic Product os $9050. The second group features 3 countries with a total population of about 185 million people and a per capita GDP of nearly 3 times the first group, at $26,500. All 7 countries feature talent pools of baseball players. All 7 countries have professional leagues of some kind. The wealthier countries of Group 2 have major leagues, minor leagues, universities, and very high level youth baseball ranging from pee wee to high school. As you might imagine, the players in Group 1 often grow up without proper equipment, and are absorbed into the US coaching system around junior high school. They are signed directly into the professional minor leagues if they show promise. Take a look at the same chart with the countries names included:

Major League ballclubs spend 10s and maybe 100s of millions of dollars every year supporting Latin ballplayers at the youth level. They dole out $2-3-4-500,000 signing bonuses for the top high school talent in these countries, and fans everywhere walk around like roosters with their chests puffed out about the crop of young talent that is now in their team's stable. The Latin influence in the Majors has been so ingrained in fans' collective consciousness that people are willing to suspend disbelief about 16 year old Dominican kids called "the next Miguel Tejada" than they are about 25 year old Japanese pitchers, who have played, at the equivalent of the AAAA level, in the Japanese professional ranks since they were 18 years old. I'm talking about Daisuke Matsuzaka, of course. He of the 2.04 ERA, 0.918 WHIP, 9.86 K-rate, and 5.97 K/BB ratio. People who have seen him call him the best pitcher of his generation in Japan. People who have seen him are drooling at the prospect of him joining their favorite club next year. Those without 1st hand knowledge of Matsuzaka are consistently comparing him to Hideki Irabu and Kazuo Matsui. Why choose the Least Common Denominator of player to set your level of expectation?

I have a theory. There are several factors that contribute to the impression of Asian players as compared with their Latin counterparts. Here are a few:

1. Latinos are fiery. Asians are passive.

This stereotype is as much a part of Western collective consciousness as any other set of cultural labels assigned to these groups. You hear former Major Leaguers in the broadcast booth use the "passionate" or "fiery" adjectives to describe a Latin player's demeanor on a nightly basis. Whenever Chien Min Wang pitches, you hear guys like Jim Kaat of the YES Network admire his stoic character on the mound, attributing it to his Asian background. He often says things like, "It seems that these Asian pitchers come over here and bring a kind of cool to the mound."

What this does in the psyche of baseball fans is build a foundation by which all other players from the same background are understood. Ichiro is a little slap hitter who can run, so that's what Japan is full of. Matsui comes as a slugger and his homers turn into doubles, so the stereotype of Japanese sluggers is now defined as some kind of failure. Latin players on the other hand get the opposite treatment. Vlad Guerrero shows 5-tool skills and the expectations are that other "fiery" Latin players will also grace the outfield of your local team with the same free swinging dominance as Vladdy. Nevermind that Guerrero is not fiery, and his aggressiveness is born of preter-natural talent that allows him to hit balls thrown behind him for home runs. There are plenty of truly fiery Latin players who swing aggressively and sport .225 averages and find themselves in the minor leagues, or out of baseball.

2. Failed analysis

The analysis of Latin talent is far more advanced than that of Asian talent among the general population. There are plenty of scouts in Asia now, after the success of Ichiro and Matsui, and the level of understanding among professional has grown exponentially. That hasn't translated to the general public because the sample size of Latin talent in the Major League ranks goes back a generation, and most casual baseball observers have grown accustomed to the hundreds of guys named Gonzales, Rodriguez, and Rivera that have been on the Game of the Week. They've literally seen thousands of Latin ballplayers, good and bad, over the years. The opposite is true of the Asian player. Until Ichiro came to the US the majority of fans had seen a few Nomo games, a handful of Korean minor leaguers, and maybe a Taiwanese or two. The total sample size was less than 10 players. Since Ichiro, a wave of players has come into the MLB ranks, which now stands in the dozens, with more in the minor leagues.

The sample size is still miniscule, and has actually hurt the casual fans' ability to accurately understand the level of talent in Asia. I'll stick with Japan for my current observation, as it is the most advanced baseball country in Asia, with the longest professional structure of any real quality. Fans have seen Ichiro win the Rookie of the Year award and the MVP. They have seen Hideki Matsui hit 30 homers for the Yankees and drive in 100+ runs every season to date. Those two players represent the only top level talent from Japan to cross the ocean. Nomo was damaged goods on arrival, and Irabu was seriously overrated by all the people that scouted him at the time. He spent about half of his career in Japan as a middle reliever with a 3.60 ERA. The best players of the last generation have not left Japan. They have been bound by contracts forcing them to perform 9 years of Japanese Professional service before they are allowed free agency, and therefore are well into their early 30's in many cases before they can leave their clubs. At that point, the money they can make on a guaranteed contract in Japan far exceeds what a Major League club is willing to spend on them. They stay.

In contrast, the Latin ballplayer is scooped up and nurtured in the American system. By 18 they are playing at A ball, or above, and Major League scouts have watched them play 100s of times. When they are ready, they are B-lined to the Major Leagues and Joe Average gets a good close look at them in their prime. The number of failed Latin players is gigantic, but we are willing to forgive those expenditures for the chance at getting the diamond in the rough. Nevermind, the fact that some Minor League All-Stars fall flat in the pros.

3. Raw versus Structured

Scouts are trusted to deliver talent into the systems of their respective teams and Latin players are the hot thing. Teams want to be the first to enter the Venezuelan market, for example, to grab up the top players in that nation of 26 million people. If the talent pool of the Dominican Republic has scouts scrambling to sign the top young talent, it doesn't take a stretch to understand that a country with 16 million more people may have a deeper selection of great players for the organization willing to spend money to find it and nurture it. There are few regulations to speaking with these players, and no professional league to stand in the way.

In Japan, for example, the aforementioned free agency system was created to maintain the economic viability of a professional league which has been around for something like 85 years. The Japanese are baseball fanatics and their are billions of dollars spent on baseball between the pros, industrial leagues, and high school kids. People stop what they're doing to watch baseball, and no one in power wants to hurt that love of the game, for money or pride. The structure in Japan does two things. It robs Major League fans of the opportunity to see legit star players in their primes. It also discourages Major League clubs from actively scouting and evaluating talent. That is, until recently. Daisuke Matsuzaka is 26 years old this week. He will be able to join a Major League club next year in his prime. He's the best pitcher of his generation, and will likely be a #1 pitcher in the Major Leagues. No one believes this because they've never seen him pitch, and there's so little precedent for a top level Japanese player to enter the Majors in his prime that only Irabu and Kaz Matsui fears come to mind.

Let's look at the players that have entered the Majors from Japan in recent years and their age at MLB debut.

Ichiro Suzuki (27 years old)

Hideki Matsui (29 years old)

Tadahito Iguchi (30 years old)

Kenji Johjima (30 years old)

Akinori Otsuka (32 years old)

Takashi Saito (36 years old)

So Taguchi (34 years old)

Hideo Nomo (26 years old)

Kaz Sasaki (28 years old)

Shigetoshi Hasegawa (30 years old)

Kazuhisa Ishii (28 years old)

Hideki Irabu (28 years old)

Kazuo Matsui (28 years old)

Tsuyoshi Shinjo (29 years old)

There are 4 or 5 other inconsequential players. Is this group a representative sample by which to draw your conclusions? The Japanese baseball ranks go back 85 years. There are currently 12 professional teams with around 25 players on each roster. In fact, if you look at this list what you see is a 1st group of players that fans have been very happy with. It includes a few All Stars, a few Rookie of the Years, and an MVP. The second group represents players who haven't provided much to their clubs and ended up villified. If you have any doubts about these players, check their stats. Even So Taguchi, who hardly jumps out at you sports a career line of .283/.330/.401 which isn't dismal. The 4 players in the 2nd group were bad. Shinjo has never been very good in Japan either. Ishii was a mediocre pitcher. Irabu was a marginally effective middle reliever who turned in 2 or 3 nice years as a starter before coming over. Kaz Matsui is a legitimate flop.

What you'll notice is that these players played their most productive years in Japan. It's common knowledge that most players achieve their peak around 25, 26, 27 years old before slowing declining. Star players decline at a far less extreme rate than marginal players. Every player on this list came to the US at the start of their decline period. After a year or so of adjustment, many of these guys were in their early 30's. Guys like Hideki Matsui, Kaz Sasaki, Tadahito Iguchi, and probably Kenji Johjima continued to produce very nice numbers for years. What you need to understand is that there are players in their primes, or entering their primes, playing in Japan that are as good as these players. We've missed out on seeing

Nobuhiko Matsunaka in the Majors. He has been an MVP and won the Japanese Triple Crown. He's 35. We've also missed out on

Kazuhiro Kiyohara, who is a legend and still hanging on to his dwindling baseball life at 39 years of age.

Michihiro Ogasawara is about to turn 33.

Kosuke Fukudome is 29. The cream of the Japanese crop is passing its prime, and new players will step into their shoes. The same restrictions apply to them, so you won't be seeing them in your living rooms unless you live in Japan. It doesn't mean that the next Ichiro isn't out there. My focus has been on Daisuke Matsuzaka because he is just such a player. It's the rare chance to see a Japanese legend in his prime. You'll see the level of play that Latin players bring to the game when they are stars and in their primes. Perhaps, this perspective will help to change the notion that somehow a region, Asia, with 3 times the baseball loving population and 3 times the wealth is inferior to the Latin talent pool. My hope is that people will be less knee jerk in their analysis of the Asian athlete, and that the wave of baseball players from this part of the world will affect the game in the same way that Latins did a generation ago.

In the end, you probably won't see too much change in Japan. It will require much better scouting and a new approach to drawing Japanese players to the US minor leagues before the pros get their hands on them for 9 years. Tomo Ohka did it. It could happen again in the future and change the way Japan handles free agency, but in the meantime there's no reason why the average American fan can't follow Japanese ball more closely. There is always room to appreciate players in their native environment. The level of competition is much higher than people generally believe. Come back to Baseball Japan to get your fill, and I will do my best to provide the background, analysis, and anything you want to hear about. Comment on the pieces and let me know what you want more of. Thanks for reading.

I return from Osaka after a nice long weekend of sightseeing, sampling of local cuisine, and contemplating the role of baseball as a part of Japanese society. My short stay in Japan's most free and individualistic city turned up more than a few glimpses of the intersection between baseball and traditional culture. I'll present a snapshot of my trip, with a special emphasis on the baseball moments that I enjoyed.

I return from Osaka after a nice long weekend of sightseeing, sampling of local cuisine, and contemplating the role of baseball as a part of Japanese society. My short stay in Japan's most free and individualistic city turned up more than a few glimpses of the intersection between baseball and traditional culture. I'll present a snapshot of my trip, with a special emphasis on the baseball moments that I enjoyed. Sampling the famous local cuisine was, of course, a highlight of the trip. I ate "okonomiyaki" which is like a pancake made in front of you on a teppanyaki grill. It's filled with various things depending on your preference, and the name actually means "whatever you like, cooked-up". I shared a seafood pancake and a cheese pancake with my wife on my first night in town. Good stuff with a frosty mug of beer.

Sampling the famous local cuisine was, of course, a highlight of the trip. I ate "okonomiyaki" which is like a pancake made in front of you on a teppanyaki grill. It's filled with various things depending on your preference, and the name actually means "whatever you like, cooked-up". I shared a seafood pancake and a cheese pancake with my wife on my first night in town. Good stuff with a frosty mug of beer. There's a lot going on in Dotonbori. Icons of Japanese popular culture are both created and celebrated in the flashy environs of the street malls. It was here that I photographed the most gigantic version of the NTT (Nippon Telephone and Telegraph) ad campaign, spanning the entire height of a building. The recent campaign touts the high speed broadband that NTT uses to provide reliable and clear service to anywhere. Ichiro Suzuki is the poster boy, in full Mariners regalia, and has his ultra-cool poster boy face in effect. My wife noted as we stared at the giant hommage to Ichiro that he's always concerned with appearances, including his endorsements, while Hideki Matsui is always playful and at ease in pajamas, traditional summer robes, or serious in his Yankee uniform.

There's a lot going on in Dotonbori. Icons of Japanese popular culture are both created and celebrated in the flashy environs of the street malls. It was here that I photographed the most gigantic version of the NTT (Nippon Telephone and Telegraph) ad campaign, spanning the entire height of a building. The recent campaign touts the high speed broadband that NTT uses to provide reliable and clear service to anywhere. Ichiro Suzuki is the poster boy, in full Mariners regalia, and has his ultra-cool poster boy face in effect. My wife noted as we stared at the giant hommage to Ichiro that he's always concerned with appearances, including his endorsements, while Hideki Matsui is always playful and at ease in pajamas, traditional summer robes, or serious in his Yankee uniform. Touring the castle and its grounds was fascinating. I'm a history buff, and I felt connected to the events of history that took place on the very ground I was standing. As I learned more, I realized that some of the most important battles in the unification of Japan were fought on the soil upon which I tread, and the blood that was shed, in some way, was responsible for the current order of things. The castle itself is beautiful and one is treated to a display of artwork, architecture, and history on each of the 8 stories of the stronghold. From the 8th story observation deck I circled around to the West to find the baseball field that I had seen from the sky the night before. It was quite large for a public park, and I could clearly make out that it was something of a huge sandlot. The juxtaposition of the ancient castle ornaments and the baseball grounds in the distance made a nice photo.

Touring the castle and its grounds was fascinating. I'm a history buff, and I felt connected to the events of history that took place on the very ground I was standing. As I learned more, I realized that some of the most important battles in the unification of Japan were fought on the soil upon which I tread, and the blood that was shed, in some way, was responsible for the current order of things. The castle itself is beautiful and one is treated to a display of artwork, architecture, and history on each of the 8 stories of the stronghold. From the 8th story observation deck I circled around to the West to find the baseball field that I had seen from the sky the night before. It was quite large for a public park, and I could clearly make out that it was something of a huge sandlot. The juxtaposition of the ancient castle ornaments and the baseball grounds in the distance made a nice photo. From the castle I bolted for the field. I wanted to see what was going on there, and what kind of facility the city of Osaka had provided for its citizens to enjoy the great game of baseball. To my surprise it was quite spartan and bombed with graffiti. There was the requisite X-rated graffiti featuring male genitals, and there was also a poor rendition of Mickey Mouse on another concrete wall. Go figure. I wasn't sure what to make of the riff-raff that was hanging around outside the grounds. There was a mix of moms with their little children, chain-smoking salarymen with big dark circles under their eyes, and even more suspicious looking characters in yellowing golf shirts kind of moping about. I stopped to take in the practice that was going on just inside the walls. There were kind of portholes cut out of the concrete backstop, and it was apparent that they were the best views in the house for the loitering fans. The guys taking batting practice against live pitching seemed to be part of a local amateur team just out for a little sunshine and some exercise.

From the castle I bolted for the field. I wanted to see what was going on there, and what kind of facility the city of Osaka had provided for its citizens to enjoy the great game of baseball. To my surprise it was quite spartan and bombed with graffiti. There was the requisite X-rated graffiti featuring male genitals, and there was also a poor rendition of Mickey Mouse on another concrete wall. Go figure. I wasn't sure what to make of the riff-raff that was hanging around outside the grounds. There was a mix of moms with their little children, chain-smoking salarymen with big dark circles under their eyes, and even more suspicious looking characters in yellowing golf shirts kind of moping about. I stopped to take in the practice that was going on just inside the walls. There were kind of portholes cut out of the concrete backstop, and it was apparent that they were the best views in the house for the loitering fans. The guys taking batting practice against live pitching seemed to be part of a local amateur team just out for a little sunshine and some exercise. I made my way around to the far side of the stadium to get a clearer look at the practice from the opening in the left field fence. It was there that I got my best view of Osaka Castle in the background, looming as the players took their reps. A handful of junior high school players, in their uniforms, were waiting around on their bicycles for their coach to arrive and start their afternoon practice. I approached them and asked if they practiced here everyday. They replied that their practices always took place on the grounds, and that they in fact played everyday in the shadow of the castle. I thought it was a powerful metaphor for the game that unified Japan on the grounds of the bloody war that defined the course of that same nation. Could any of those warlords, or any of their soldiers, have imagined that the battlefield where they lost their lives and struggled for ultimate control of the riches of Japan would one day be a symbol of populist life, and an arena dedicated to a game brought to Japan by missionaries centuries later.

I made my way around to the far side of the stadium to get a clearer look at the practice from the opening in the left field fence. It was there that I got my best view of Osaka Castle in the background, looming as the players took their reps. A handful of junior high school players, in their uniforms, were waiting around on their bicycles for their coach to arrive and start their afternoon practice. I approached them and asked if they practiced here everyday. They replied that their practices always took place on the grounds, and that they in fact played everyday in the shadow of the castle. I thought it was a powerful metaphor for the game that unified Japan on the grounds of the bloody war that defined the course of that same nation. Could any of those warlords, or any of their soldiers, have imagined that the battlefield where they lost their lives and struggled for ultimate control of the riches of Japan would one day be a symbol of populist life, and an arena dedicated to a game brought to Japan by missionaries centuries later.